Key words

- Bowel preparation

- Colonoscopy

- Split timing preparation

- Adenoma detection rate

- Colorectal cancer

Abbreviations

ADR – Adenoma detection rate

BBPS – Boston bowel preparation scale

FIT – Faecal immunochemical test

LRD – Low residue diet

PEG – Polyethyl glycol

PCCRC – Post colonoscopy colorectal cancer

Learning points

- Timing is a key factor in adequate bowel preparation. Most endoscopy units in the UK split bowel preparation for afternoon procedures, but not for morning procedures.

- Patient adherence impacts bowel preparation quality, which can be improved by enhanced educational interventions.

- In the setting of previous poor preparation, high volume PEG and adjuvant stimulant laxatives improve cleansing and the rate of adequate preparation at subsequent colonoscopy.

Case

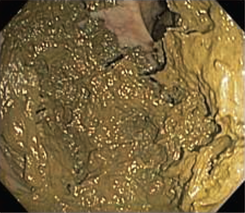

A 64-year-old male is referred urgently to the gastroenterology clinic with an elevated faecal immunochemical test (FIT). He states his bowel is always “sluggish” but recently he has been opening his bowel less frequently, less than once per week. He has not noticed any rectal bleeding, but his FIT is elevated at 235µg/g. He has a past medical history of angina, type 2 diabetes mellitus, has chronic back pain and he had an open appendicectomy following a perforation. He takes codeine, paracetamol, amitriptyline, metformin, gliclazide, aspirin, ramipril, and bisoprolol. His colonoscopy is performed the following week. He received 2L of Polythylene Glycol (PEG) with ascorbate the day before the test and followed the low residue diet for 24 hours. He had fasted from lunch time the previous day. His endoscopy was abandoned in the transverse colon due to poor bowel preparation.

Figure 1 – View of transverse colon at colonoscopy

Introduction

- Poor bowel preparation for colonoscopy is common, seen in up to 25% of procedures1.

- Inadequate cleansing prolongs procedural time, reduces caecal intubation and often necessitates repeat endoscopy. It is also a risk factor for missed polyps and is one of the main causes of post colonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC), associated with a four-fold increase in PCCRC2.

- Ensuring adequate bowel preparation is a vital step to prevent missing significant lesions3.

Grading metrics

- Assessing the quality of preparation using a reliable metric permits consistency of reporting between endoscopists and helps to indicate the likelihood of missed lesions3.

- Categorical scales, such as the Aronchick scale, are often used. However, segmental scales that divide the bowel into sections provide more consistent reporting between endoscopists and correlate more closely with adenoma detection rate (ADR)3.

- Several segmental scales have been devised, but the most validated scale is the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), with a high interobserver reliability. This grades preparation on withdrawal after all washing and cleansing has been conducted, with each segment scoring between 0-3 (0 being the worst)4.

- A BBPS of <2 is associated with a 10-21% risk of missing any polyps and a 4-10% likelihood of missing an advanced adenoma3 5.

- A modified BBPS score for artificial intelligence interpretation of preparation has been devised, with reported quality of cleansing correlating with ADR6. This raises the potential of automation of grading of preparation for the future.

Adherence

- Bowel preparation is challenging and is often described by patients as worse than the procedure itself. Adherence is, however, a determinant of the quality of preparation7.

- A variety of educational interventions to support adherence have been investigated, including enhanced written instructions, videos, and mobile phone applications8. These have consistently demonstrated improvement in preparation, with more intensive interventions yielding better results9.

- The use of motivational, patient friendly instructions is the minimum of care, and additional interventions such as educational videos or mobile phone applications should also be considered 10.

- Dedicated pre-endoscopy face-to-face assessment and explanation of instructions may be the best approach for patients who are at the greatest risk of poor preparation11.

Timing of bowel preparation

- The closer the preparation is consumed to the procedure, the better the cleansing, with optimal timing 4-5 hours prior to the test10.

- Same day and split preparation (where the dose is split between the day before and on the day of the procedure) have similar efficacy but are both superior to day-before preparation. Same day or split preparation are recommended within recent European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines 10.

- Split preparation is used by most units in the UK for afternoon and evening appointments, however 93% of units provide day-before preparation for morning procedures12. This leaves an important opportunity to make significant improvements in preparation quality. When given the choice, patients are willing to wake early to have split preparation, and sleep quality is not significantly affected13 14.

Can poor preparation be predicted?

- Risk factors for poor preparation have been identified. Increasing age, male sex, incomplete ingestion of the purgative, medications associated with constipation (opioids, calcium channel blockers and amitriptyline), previous abdominal surgery, diabetes mellitus, constipation, and inpatient status, have all been associated with an increased likelihood of suboptimal cleansing15-18.

- Three predictive scores have been developed which stratify the risk of poor preparation. However, a study undertaken by Gimeno-Garcia et al did not demonstrate improvement in cleansing for an augmented bowel preparation regime for patients assessed as being at high risk of poor cleansing15-17.

What to do when a patient has poor bowel preparation?

- Initially, a review of the patient’s medical history, colonoscopy indication, and adherence to preparation regime is warranted. In an elderly, frail and heavily comorbid patient, further endoscopic investigation may not be warranted, and less invasive cross-sectional imaging may be appropriate. Alternatively, for certain indications, sub optimal preparation may still allow the clinical query to be answered.

- Subsequently, the assessment of the patient’s understanding and adherence to the preparation regime is required. If a patient took the preparation incorrectly, the same preparation with a clear explanation and additional educational interventions may suffice. However, if the patient did not manage to complete the prior preparation, increasing the volume of liquid is unlikely to be successful. Ultra-low volume 1 litre PEG with ascorbate was as effective as a 2 litre PEG regime19, and is an option for patients who struggle to complete the bowel preparation regime. Recent data also indicates it is useful in some more difficult to prepare groups, such as older patients and inpatients20 21.

- Optimising the timing of preparation will be beneficial.

- Several studies have demonstrated that increasing the volume of purgative improves cleansing quality in patients with prior poor preparation. An augmented regime with 4 litres of PEG had a 13.7% lower rate of inadequate preparation than a 2 litre PEG augmented regime22. Adjuvant laxatives are also beneficial with several studies demonstrating the benefit of senna/bisacodyl used in conjunction with a PEG based regime23. At our centre, in the setting of prior poor bowel preparation despite adherence to 2 litre PEG with ascorbate, an augmented regime is utilised. This consists of 4 litre PEG given with split timing, preferentially for afternoon or evening appointments (2 litres the day before, 2 litres to be completed 5 hours prior to test), 7 days of senna 15mg od nocte, and 5 days low residue diet (LRD).

Diet and fasting

- LRD appears as effective as a liquid only diet pre-endoscopy, but is better tolerated. Evidence appears to indicate that prolonging the LRD for unselected patients for more than one day does not appear to improve cleansing, however it is often used in augmented regimes24.

- There is considerable variation in length of fast in the UK prior to endoscopy, with the median advised fasting time being 23.5 hours12.

- A study by Alvarez-Gonzalez compared a 24-hour fast with a 16-hour fast before colonoscopy. Both groups had completed 4 days of LRD and were given 4 litres of split dosing PEG. Adequate cleansing was seen in 95.7% of the 16-hour fast group compared with 89.1% in the 24-hour fasting group, indicating the potential to shorten fasting times for patients prior to colonoscopy25.

Discussion

- Bowel preparation for colonoscopy is the first key step to a good quality examination.

- Split and same day bowel preparation should be undertaken universally.

- Taking steps to improve adherence with patient educational interventions is effective.

- The most effective management of those at high risk of poor bowel preparation is still unclear, however, adjuvant laxatives and split dose high volume PEG has been demonstrated to improve preparation for repeat colonoscopies.

Author Biographies

Dr Mo Thoufeeq

Mo Thoufeeq is a consultant gastroenterologist with an interest in GI endoscopy. He is an honorary senior clinical lecturer at the University of Sheffield. He is an elected member of the BSG Endoscopy clinical research committee. He is an active member of the BSG endoscopy quality improvement programme (EQIP) team and the lead for Yorkshire.

He is a Bowel cancer screening programme (BSCP) accredited colonoscopist and a faculty of Sheffield endoscopy training centre.

He is very keen on training, being a member of standard setting group of Specialty Certificate Examination (SCE) gastroenterology, Royal College of Physicians (RCP), UK. He offers a fellowship programme in EMR in Sheffield. He is involved with training internationally and is the BSG International committee’s communication lead. He has run endoscopy courses in India, Malta, and in Cairo.

Dr Thomas Archer

Dr Thomas Archer is specialist trainee in gastroenterology, hepatology and general internal medicine in South Yorkshire. He is interested in pursuing a career in advanced gastrointestinal endoscopy. He recently completed an academic and endoscopy fellowship at Sheffield University, where he is an honorary clinical teacher. During this time, he also developed his experience in advanced lower gastrointestinal endoscopy. His research centred around lower gastrointestinal endoscopy with a special interest in bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Dr Archer previously worked in India before commencing his specialist training.

CME

Endoscopy Workforce Education and Training

30 January 2024

Investigations of IDA – When, how and when not to!

03 January 2024

Masterclass: Endoscopic foreign body removal – what you need to know

11 December 2023

- Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, et al. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73(6):1207-14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.051 [published Online First: 2011/04/08]

- Subramaniam K, Ang PW, Neeman T, et al. Post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers identified by probabilistic and deterministic linkage: results in an Australian prospective cohort. BMJ Open 2019;9(6):e026138. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026138 [published Online First: 2019/06/21]

- Clark BT, Protiva P, Nagar A, et al. Quantification of Adequate Bowel Preparation for Screening or Surveillance Colonoscopy in Men. Gastroenterology 2016;150(2):396-405; quiz e14-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.041 [published Online First: 2015/10/09]

- Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, et al. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69(3 Pt 2):620-5. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.057 [published Online First: 2009/01/10]

- Kluge MA, Williams JL, Wu CK, et al. Inadequate Boston Bowel Preparation Scale scores predict the risk of missed neoplasia on the next colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87(3):744-51. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.06.012 [published Online First: 2017/06/23]

- Lee JY, Calderwood AH, Karnes W, et al. Artificial intelligence for the assessment of bowel preparation. Gastrointest Endosc 2022;95(3):512-18.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.11.041 [published Online First: 20211208]

- Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96(6):1797-802. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03874.x

- Li P, He X, Yang X, et al. Patient education by smartphones for bowel preparation before colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;37(7):1349-59. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15849 [published Online First: 20220413]

- Chang CW, Shih SC, Wang HY, et al. Meta-analysis: The effect of patient education on bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Endosc Int Open 2015;3(6):E646-52. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392365 [published Online First: 2015/06/24]

- Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline – Update 2019. Endoscopy 2019;51(8):775-94. doi: 10.1055/a-0959-0505 [published Online First: 2019/07/11]

- Rosenfeld G, Krygier D, Enns RA, et al. The impact of patient education on the quality of inpatient bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24(9):543-6. doi: 10.1155/2010/718628

- Archer T, Shirazi-Nejad AR, Al-Rifaie A, et al. Is it time we split bowel preparation for all colonoscopies? Outcomes from a national survey of bowel preparation practice in the UK. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2021;8(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000736

- Radaelli F, Paggi S, Repici A, et al. Barriers against split-dose bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gut 2017;66(8):1428-33. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311049 [published Online First: 2016/04/19]

- Unger RZ, Amstutz SP, Seo DH, et al. Willingness to undergo split-dose bowel preparation for colonoscopy and compliance with split-dose instructions. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55(7):2030-4. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1092-x [published Online First: 2010/01/16]

- Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(5):501-6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.037 [published Online First: 2012/01/10]

- Dik VK, Moons LM, Hüyük M, et al. Predicting inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy in participants receiving split-dose bowel preparation: development and validation of a prediction score. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81(3):665-72. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.09.066 [published Online First: 2015/01/17]

- Gimeno-García AZ, Baute JL, Hernandez G, et al. Risk factors for inadequate bowel preparation: a validated predictive score. Endoscopy 2017;49(6):536-43. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-101683 [published Online First: 2017/03/10]

- Mahmood S, Farooqui SM, Madhoun MF. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30(8):819-26. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001175

- Bisschops R, Manning J, Clayton LB, et al. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus 2 L polyethylene glycol + ascorbate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy 2019;51(1):60-72. doi: 10.1055/a-0638-8125 [published Online First: 20180719]

- Baile-Maxia S, Amlani B, Martínez RJ. Bowel-cleansing efficacy of the 1L polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation NER1006 (PLENVU) in patient subgroups in two phase III trials. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021;14:17562848211020286. doi: 10.1177/17562848211020286 [published Online First: 20210624]

- Maida M, Sinagra E, Morreale GC, et al. Effectiveness of very low-volume preparation for colonoscopy: A prospective, multicenter observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2020;26(16):1950-61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i16.1950

- Gimeno-García AZ, Hernandez G, Aldea A, et al. Comparison of Two Intensive Bowel Cleansing Regimens in Patients With Previous Poor Bowel Preparation: A Randomized Controlled Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112(6):951-58. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.53 [published Online First: 2017/03/14]

- Vradelis S, Kalaitzakis E, Sharifi Y, et al. Addition of senna improves quality of colonoscopy preparation with magnesium citrate. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15(14):1759-63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1759

- Nguyen DL, Jamal MM, Nguyen ET, et al. Low-residue versus clear liquid diet before colonoscopy: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83(3):499-507.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.09.045 [published Online First: 2015/10/13]

- Alvarez-Gonzalez MA, Pantaleon MA, Flores-Le Roux JA, et al. Randomized Clinical Trial: A Normocaloric Low-Fiber Diet the Day Before Colonoscopy Is the Most Effective Approach to Bowel Preparation in Colorectal Cancer Screening Colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum 2019;62(4):491-97. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001305