Author names: Dr Prarthana Thiagarajan1, Dr Brinder Mahon2, Professor Dhiraj Tripathi2,3,

Author institutions:

1 Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

2 University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

3 Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy, University of Birmingham

Statement of any potential perceived conflicts of interest (include name(s) of author(s) to whom they apply):

Professor Tripathi – Speaker fees for WL Gore & Associates.

Key words

1. Portal hypertension

2. Gastric varices

3. Cirrhosis

4. Variceal haemorrhage

5. Endoscopy

Abbreviations

TIPSS – Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt

VBL – Variceal band ligation

ECI – Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection

EUS – Endoscopic ultrasound

BRTO – Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration

PARTO – Plug assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration

CARTO – Coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration

Learning points

- Gastric varices are present in approximately 20% of patients with established portal hypertension. While rarer than oesophageal variceal bleeding, gastric variceal bleeding is associated with higher mortality.

- First line treatment in acute bleeding is endoscopic injection therapy; where available, endoscopic ultrasound-guided injection therapy may be offered as additional or alternative haemostatic treatment. Pre-emptive TIPSS may be considered in selected patients at high risk of re-bleeding following endotherapy.

- In endoscopically refractory bleeding, endovascular approaches may be planned according to local expertise following venous mapping studies. We recommend a multidisciplinary approach and discussion with a specialist liver unit to guide definitive radiological treatment.

Background

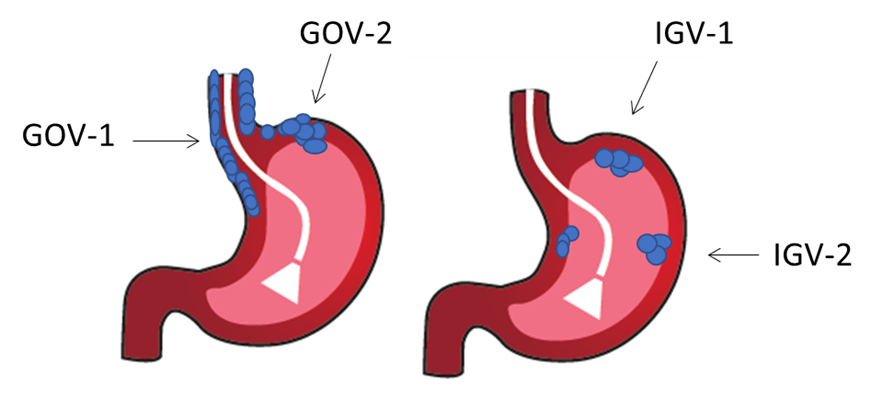

Management of bleeding gastric varices remains challenging. While less common than oesophageal variceal bleeding, gastric varices are associated with more severe haemorrhage, increased rebleeding risk and higher mortality [[i], [ii], [iii]]. Prevalence of gastric varices in cirrhotic portal hypertension is estimated to be 15-25% [3, [iv]]. Bleeding risk is a composite function of varix size, wall tension, portal pressure and severity of underlying liver disease. Bleeding from gastric varices occurs at lower portal pressure gradients than oesophageal variceal bleeding. Gastric varices can also occur in the absence of cirrhosis, usually in the context of splenic vein thrombosis. This is termed segmental or ‘left-sided’ portal hypertension. The Sarin classification of gastric varices is shown in Figure 1.

Paucity of robust evidence-base for optimal endoscopic management, together with the advent of radiological and EUS-guided techniques, complicates decision-making for patients with gastric variceal bleeding (GVB), as well as approaches to primary and secondary prophylaxis.

In this article, we present our recommendations for managing the patient with GVB, and discuss evidence to-date for approaches to haemostasis, primary and secondary prophylaxis.

Acute Bleeding from Gastric Varices

Patients with established portal hypertension presenting with signs of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage should be managed in line with current BSG guidelines [v]. Briefly, this will consist of airway protection (if active haematemesis), volume resuscitation, broad spectrum antibiotics, splanchnic vasopressors and selected blood product administration. We suggest the use of viscoelastic tests, such as thromboelastography (TEG) to guide blood product replacement, as this more accurately addresses haemostatic balance in liver disease and reduces product requirement [vi]. For blood product administration in uncontrolled bleeding, case-by-case decisions in liaison with a haematologist are advised. [vii].

Urgent endoscopic assessment is required after resuscitation and optimisation. Once GVB is confirmed endoscopically, therapeutic options include:

- Endoscopic injection therapy

- EUS-guided injection +/- coil therapy

- Long-term NSBB.

- Radiological procedures e.g. TIPSS, BRTO, PARTO, CARTO, splenic artery embolisation

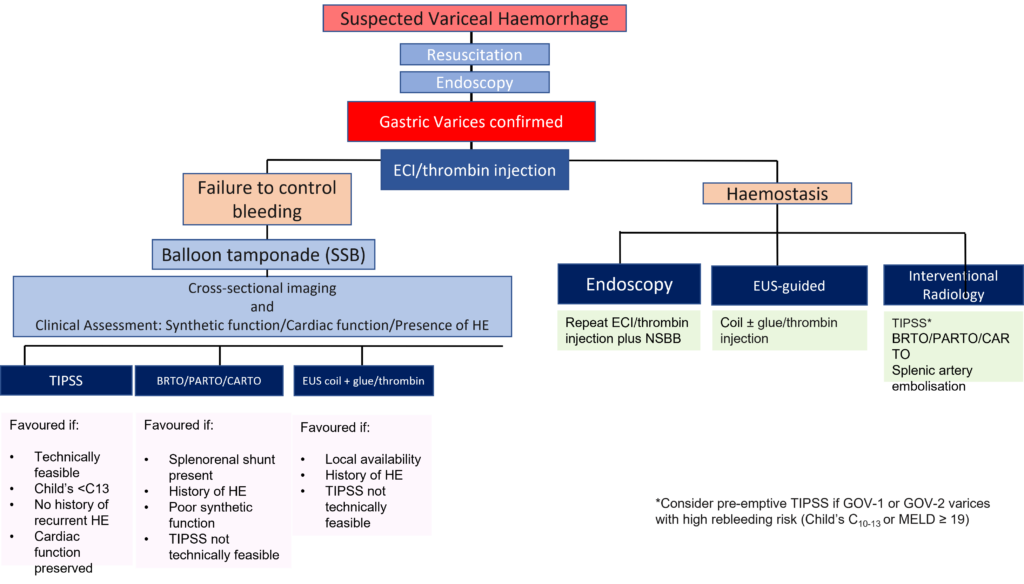

Available techniques, their relative merits and drawbacks are summarised in Table 1. A proposed algorithm for management of GVB is shown in Figure 2.

Endoscopic Haemostasis

Sclerotherapy with n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection directly into gastric varices was first described in 1986 [viii] and has since become standard of care. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection (ECI) is favoured over band ligation for non-GOV-1 gastric varices as randomised studies have consistently demonstrated superior haemostasis rates, lower rebleeding risk and reduced mortality [[ix],[x]]. In the event of uncontrolled bleeding, balloon tamponade with a Sengstaken Blakemore or Linton Nachlas tube is recommended as a bridge towards definitive treatment. Removable oesophageal stents such as the Danis stent do not have a role in GVB, as they do not offer tamponade of gastric varices.

While ECI is an effective treatment for GVB, it carries significant risk of systemic embolisation which can be fatal [xi]. Local procedure-related complications include gastric ulcer formation, needle adherence to the varix after injection, blockage of the injection catheter and glue adhesion to the endoscope [xii]. More recently, human thrombin injection has been used as an alternative to ECI, with initial haemostasis rates of 92- 94% reported [[xiii],[xiv]]. In 2020, a prospective randomised trial compared thrombin with ECI in 68 patients with GVB, reporting similar haemostasis and rebleeding rates, but a significantly lower adverse event rate with thrombin injection [xv], findings confirmed in a meta-analysis of 11 studies evaluating thrombin use in GVB [xvi]]. The authors use human thrombin 500IU/ml in prefilled syringes (Tisseel®, Baxter Healthcare, Newbury, UK) and typically administer 1000 IU (i.e. 2 aliquots) per session. After initial haemostasis is achieved, our practice is to arrange two elective endoscopy sessions for further thrombin injection.

EUS-guided intervention

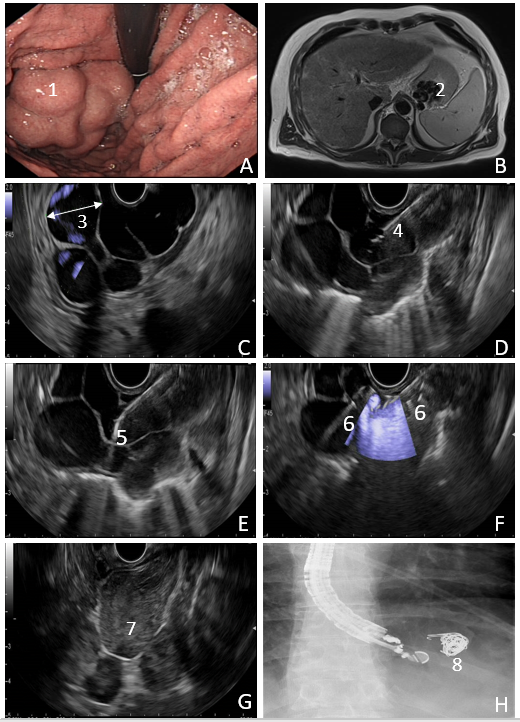

EUS-guided embolisation therapy and glue (or thrombin) injection ± coil placement has gained momentum in recent years. This approach has yielded excellent results: in a retrospective study of 152 patients, a 99% haemostasis rate was reported, with a rebleeding rate of 16% and embolisation rate of 0.7% [xvii]. In our local experience with 10 EUS-guided interventions (either thrombin alone or in conjunction with Nester coils) in 6 patients with a median follow up time of 9 months, we recorded zero 30-day mortality with no reported early rebleeding [xviii]. With combination therapy, coil injection provides a scaffold for glue adherence, which may in principle reduce distal embolisation risk. EUS also offers the added advantage of confirming immediate varix thrombosis using Doppler assessment. Figure 3 illustrates EUS-guided haemostasis in GVB.

EUS-guided therapies have not been prospectively compared with ECI or thrombin injection in randomised studies. This remains an unmet need. Availability of EUS providers and advanced nature of training required to provide EUS-guided haemostasis may have limited its availability. Nonetheless, high technical success rate, low rebleeding risk and reduced adverse event rate are likely to render this approach increasingly popular with time.

Coils are made of metal alloy and contain radially-extending synthetic fibres, which induce clot formation and haemostasis. Coil selection is based on the size and diameter of the varix and is intended to slow blood flow and provide a nidus for clot formation.

Radiological techniques

Single phase, portal phase CT imaging in patients presenting with GVB can provide a good appreciation of the size and site of oesophagogastric varices. In addition, this facilitates mapping of portosystemic shunts and splanchnic vein thrombosis burden, and will guide definitive radiological management in the event of rebleeding.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) provides definitive portal pressure reduction. Most of the evidence supports the use of early or pre-emptive TIPSS for patients with GOV-1 and GOV-2 varices with high rebleeding risk [i], as well as its use as rescue therapy for patients with refractory bleeding [5]. In one study evaluating TIPSS versus ECI for secondary prophylaxis of GVB, TIPSS was associated with a significantly lower rate of rebleeding (11 vs 38%) [ii]. Adjuvant transvenous embolisation of varices may be performed simultaneously, with a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs confirming reduced odds of rebleeding with this combined approach [iii].TIPSS placement can precipitate encephalopathy, hepatic synthetic dysfunction and cardiac decompensation. Thus, TIPSS use is limited to selected patients, in whom benefits are likely to outweigh risk.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is an endovascular procedure employing use of an indwelling balloon to occlude a splenorenal shunt in order to reduce variceal inflow, together with sclerosing agents and coils for varices obliteration. The advantage to BRTO is that it does not divert blood flow away from the portal circulation; thus, synthetic function is preserved and encephalopathy is not precipitated. It is an effective haemostatic technique in patients with accessible shunts, particularly where TIPSS is contraindicated or technically infeasible. The technical success rate of BRTO in GVB is 77%–100%, with rebleeding rates of up to 14% reported [iv]. Baveno VII guidance currently recommends BRTO as an alternative to TIPS or endotherapy for GVB with GOV-2 or IGV-1 varices, where local expertise is available [v].

Modifications of the BRTO technique currently gaining traction include plug-assisted and coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO and CARTO), in which gelfoam slurry or coils respectively, are deployed to obliterate gastric varices. However, an increase in portal pressure gradient is associated with these techniques, which can aggravate development of oesophageal varices and ascites [vi]. Thus, pre-existing oesophageal varices should be treated before BRTO or associated techniques are undertaken.

In non-cirrhotic portal hypertension secondary to splenic vein thrombosis, due consideration should be given to splenic artery embolisation +/- prophylactic splenectomy in the event of recurrent GVB.

Primary prophylaxis

The approach to primary prophylaxis for patients with incidentally detected gastric varices is controversial. Recent Baveno VII consensus guidelines advocate non-selective beta-blockade (NSBB) for patients with GOV-2 or IGV-1 varices, with a view to prevention of decompensation [23]. One small study comparing ECI to NSBB for primary prophylaxis found a significantly lower rebleeding rate with ECI, although no survival advantage was observed [vii]. In the absence of high-quality data to confirm superiority of endoscopic methods, NSBB alone is currently recommended for primary prophylaxis.

Secondary Prophylaxis

There is no consensus to date regarding secondary prophylaxis of GVB. Current UK guidelines advise endoscopic surveillance with ECI as needed for GOV-2 or IGV-1 varices, although the optimal interval for follow-up endoscopy is unclear [5]. A recent meta-analysis of 9 RCTs evaluating efficacy of available treatments concluded that BRTO was associated with a lower rebleeding risk compared with ECI and NSBB [viii]. Conversely, NSBB alone was associated with higher risk of rebleeding and mortality compared with ECI monotherapy, combination therapy (ECI plus NSBB), EUS-guided therapies, BRTO and TIPSS. While BRTO and EUS-guided interventions ranked highest in terms of preventing mortality, this was supported by low certainty evidence. Robust, multi-centre randomised data comparing available interventions is required to clarify the optimal method for secondary prophylaxis in GVB.

Conclusions

GVB is an uncommon but frequently life-threatening complication of portal hypertension. Its management is increasingly complex with the advent of advanced endoscopic and radiological interventions for haemostasis. While ECI remains the cornerstone of initial management, a multidisciplinary approach in conjunction with a tertiary liver unit is advised in the event of recurrent bleeding, to guide definitive therapy according to patients’ individual risk profile and local expertise. Early cross-sectional imaging is crucial to guide further management, which can include TIPSS, BRTO/PARTO/CARTO or EUS-guided interventions.

Gastric varices are classified into four types based on their location within the stomach and their continuity with oesophageal varices:

Gastroesophageal varix (GOV) type 1: Extension of oesophageal varices along lesser curve of the stomach

Gastroesophageal varix type (GOV) type 2: Extension of oesophageal varices along greater curve and extending towards the fundus

Isolated gastric varix (IGV) type 1: isolated cluster of varices in the fundus

Isolated gastric varix type (IGV) type 2: isolated cluster of varices elsewhere in the stomach

| Intervention | Technique | Pros | Cons |

| Endoscopic Cyanoacrylate/thrombin Injection | Endoscopically guided needle injection of cyanoacrylate glue or human thrombin directly into varix | Available in most centres

| Glue embolisation

Re-bleeding risk

Ulcer formation over varix |

| EUS-guided coil ± glue/thrombin injection | Echo-endoscope used to directly inject coil and tissue adhesive(s) or thrombin into varix | Doppler assessment to confirm varix obliteration.

Combination therapy reducing volume of glue required. | Limited to centres with expertise

Advanced training required |

| Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Stent-Shunt (TIPSS) | Interventional Radiology-guided stent insertion to reduce portosystemic gradient. | Definitive reduction in portal pressure

Effective reduction of rebleeding risk

Rescue procedure if endotherapy failure | Limited availability

Encephalopathy risk

Risk of cardiac and hepatic decompensation

Not usually possible if cavernomatous transformation of chronic portal vein thrombosis is present.

Not effective in total splenic vein thrombosis or left sided portal hypertension

|

| Balloon-occluded, plug-assisted or coil-assisted Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO, PARTO, CARTO) | Interventional Radiology-guided balloon, coil assisted or plug assisted occlusion of gastro-renal shunt | Effective reduction of bleeding risk

Effective reduction of rebleeding risk

No encephalopathy risk

| Requirement for gastro-renal shunt

Limited availability

Portal vein thrombosis

Risk of aggravating oesophageal/ectopic varices and ascites from increased portal pressure. |

| Partial splenic artery embolisation | Interventional radiology guided coil embolisation of splenic artery | Effective for treatment of left-sided portal hypertension/splenic vein thrombosis | Post-embolisation syndrome (self-limiting abdominal pain and fever)

Risk of splenic infarction, abscess or rupture is low. |

Figure 2. Algorithm for management of Gastric Variceal Bleeding

Abbreviations: TIPSS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt; ECI, endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection; EUS, Endoscopic Ultrasound; BRTO, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration; PARTO, plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration; CARTO, coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration; SSB, Sengstaken Blakemore tube.

Note: Danis stents do not have a role in the management of gastric variceal bleeding.

Figure 3. Large IGV1 gastric varices treated by Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided coil and thrombin embolisation. A large gastric variceal complex measuring 5cm high in the gastric cardia. Vessels ranging in size from 11mm to 19.5mm. EUS guided 19G access was obtained with placement of three 20mmx14cm nester coils followed by two 12mmx14cm and one 10mmx14cm. This was followed by injection of a total of 2500 units of thrombin. There was clear obliteration of blood flow on doppler ultrasound at the end of the procedure with clot formation. A) A retroflexed standard endoscopic view of the varix (1). B) A T1 MRI image displaying the large complex gastric fundal varix, however importantly further establishing the single nature of the variceal complex (2). C) Endosonographic view of the largest vessel measured 19.5mm within the variceal complex (3). D) 19G needle placed within the varix (4) and E) tip of embolization coil just exiting the needle (5). F) Multiple coils now placed (6) G) Echogenic thrombus demonstrated with the entire variceal complex without any flow detected on doppler ultrasound demonstrating obliteration and thus no requirement of a second site for embolization within this variceal complex (7). H) Fluoroscopic imaging showing deployed coils although it should be noted that fluoroscopic imaging in our series is not required (8).

Author Biographies

Dr Prarthana Thiagarajan

Dr Prarthana Thiagarajan is a Consultant Hepatologist at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. She trained in Gastroenterology and Hepatology in the East Midlands rotation, completing a 12-month advanced fellowship in transplant Hepatology at the Birmingham Liver Unit in 2022. She received a PhD from the University of Nottingham in 2021. Her specialist interests include metabolic liver disease, portal hypertension and endohepatology.

Dr Brinder Singh Mahon

Dr Brinder Singh Mahon OBE, is a Consultant Radiologist at University Hospitals Birmingham, and a longstanding expertise in Endscopic Ultrasound intervention and HPB Imaging. He is a multiple author, speaker and EUS trainer, leading one of the largest EUS centres in the UK. He is the previous Chair of the UK and Ireland EUS Users Group.

Professor Dhiraj Tripathi

Professor Dhiraj Tripathi is a Consultant Hepatologist, Honorary Professor and Clinical Director of Research at University Hospitals Birmingham. He has particular interests in liver transplantation, portal hypertension and vascular liver disease. He is lead author of the BSG guidelines on variceal bleeding in cirrhosis and TIPSS in the management of portal hypertension, and is actively involved in two further BSG guidelines in development. He is an elected member of the BSG Council. Other committee roles include member of NICE Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee and Regional Councillor for RCPSG. International collaborations include membership of EASL-VALDIG vascular liver disease interest group, and of the scientific advisory board of Baveno VII. He is Chief Investigator of national clinical trials on portal hypertension. He has over 80 publications in peer review journals and book chapters.

CME

Endoscopy Workforce Education and Training

30 January 2024

Investigations of IDA – When, how and when not to!

03 January 2024

Masterclass: Endoscopic foreign body removal – what you need to know

11 December 2023

1 Wani ZA, Bhat RA, Bhadoria AS et al. Gastric varices: Classification, endoscopic and ultrasonographic management. J Res Med Sci 2015; 20: 1200–1207

2 Chang YJ, Park JJ, Joo MK, et al. Long-term outcomes of prophylactic endoscopic histoacryl injection for gastric varices with a high risk of bleeding. Digest Dis Sci 2010; 55:2391–2397

3 Sarin, S.K.; Lahoti, D.; Saxena, S.P et al. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: A long-term follow-up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology 1992,16, 1343–1349

4 Mumtaz K, Majid S, Shah H et al. Prevalence of gastric varices and results of sclerotherapy with N-butyl 2 cyanoacrylate for controlling acute gastric variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Feb 28;13(8):1247-51.

5 Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut 2015;64: 1680–704.

6 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and management of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2022 May;76(5):1151-1184

7 Mohanty A, Kapuria D, Canakis A et al. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in acute variceal haemorrhage: Results from a multicentre cohort study. Liver Int. 2021 Aug;41(8):1901-1908.

8 Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H et al. Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate. Endoscopy. 1986 Jan;18(1):25-6.

9 Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS et al. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology 2001; 33:1060–4.

10 Tan P-C, Hou M-C, Lin H-C, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology 2006; 43:690–7.

11 Burke MP, O’Donnell C, Baber Y. Death from pulmonary embolism of cyanoacrylate glue following gastric varix endoscopic injection. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2017 Mar;13(1):82-85

12 Guo YW, Miao HB, Wen ZF et al. Procedure-related complications in gastric variceal obturation with tissue glue. World J Gastroenterol. 2017 Nov 21;23(43):7746-7755.

13 Ramesh J, Limdi JK, Sharma V, et al. The use of thrombin injections in the management of bleeding gastric varices: a single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;68:877–82

14 McAvoy NC, Plevris JN, Hayes PC. Human thrombin for the treatment of gastric and ectopic varices. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:5912–17.

15 Lo GH, Lin CW, Tai CM et al. A prospective, randomized trial of thrombin versus cyanoacrylate injection in the control of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopy 2020 Jul;52(7):548-555

16 Bhurwal A, Makar M, Patel A et al. Safety and Efficacy of Thrombin for Bleeding Gastric Varices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Mar;67(3):953-963.

17 Bhat YM, Weilert F, Fredrick RT et al. EUS-guided treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue: a large U.S. experience over 6 years (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 83: 1164–117

18 Orourke J, Shekhar C, Tripathi D, et alPWE-093 Treatment of gastric fundal varices with EUS guided embolisation combining coil placement with thrombin injection Gut 2018;67:A118-A119.

19 Garcia-Pagán JC, Di Pascoli M, Caca K, et al. Use of earlyTIPS for high-risk variceal bleeding: results of a post-RCT surveillance study. J Hepatol 2013;58:45–50.

20 Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, et al. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy 2007;39:679–85

21 Qi X, Liu L, Bai M, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in combination with or without variceal embolization for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:688–96.

22 Goral V, Yılmaz N. Current approaches to the treatment of gastric varices: glue, coil application, tips, and BRTO. Medicina 2019;55:335

23 de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G et al. Baveno VII – Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022 Apr;76(4):959-974.

24 Park JW, Yoo JJ, Kim SG et al. Change in Portal Pressure and Clinical Outcome in Cirrhotic Patients with Gastric Varices after Plug-Assisted Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration. Gut Liver. 2020 Nov 15;14(6):783-791.

25 Mishra SR, Sharma BC, Kumar A et al. Primary prophylaxis of gastric variceal bleeding comparing cyanoacrylate injection and beta-blockers: a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2011 Jun;54(6):1161-7

26 Osman KT, Nayfeh T, Abdelfattah AM et al. F. Secondary Prophylaxis of Gastric Variceal Bleeding: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Liver Transpl. 2022 Jun;28(6):945-958