Author names: Lisa McNeill, Dr Stuart McPherson

Author institutions: Liver Unit, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Introduction

Upper GI Haemorrhage is a common presentation to hospital and has an overall mortality rate of 10% (1). The 6-week mortality rate following first episode of variceal bleeding is 20% (2).

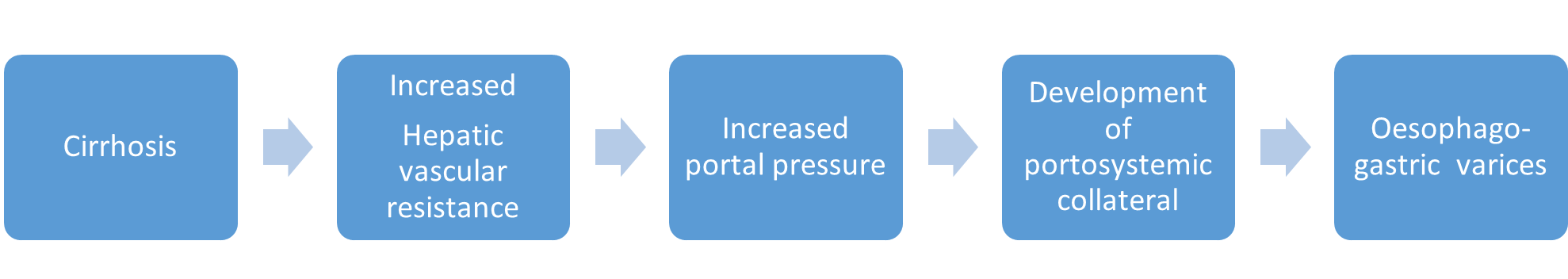

Varices develop due to a progressive rise in portal pressure that results in the development of a collateral circulation allowing blood from the portal system to be shunted into the systemic circulation (2). Oesophago-gastric varices develop as a result and are at risk of bleeding (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Development of oesopho-gastric varices (3)

Patients admitted with GI bleeding should be managed in a centre offering variceal band ligation, balloon tamponade, and management of gastric variceal bleeding (2). All patients should have a full history elicited and examination completed, particularly focussing on signs of cirrhosis. Given the high mortality of patients with GI bleeding, they should be managed in a high dependency setting with continuous monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure. Airway protection is critical and patients with reduced conscious level or ongoing active vomiting of blood should be intubated because aspiration in this setting has a mortality rate of close to 100%(4). Patients should have investigations and resuscitation according to the BSG decompensated cirrhosis (5) and GI bleeding bundles (6).

Terlipressin and antibiotics should be administered (4). Recent guidance suggests against preprocedural platelet or FFP transfusions in patients with stable cirrhosis undergoing gastrointestinal procedures, although suggests discussion with haematologist in patients with severe derangement in coagulation or thrombocytopenia (7). Patients presenting with variceal bleeding should proceed to endoscopy ideally within 12 hours of presentation. If the patient is clinically unstable then the endoscopy should be performed as soon as this is safely possible to do so, with anaesthetic support (4). Airway protection prior to endoscopy is strongly recommended in patients with variceal bleeding because these patients are at high risk of aspiration (4). The endoscopy procedures can be challenging, lengthy, and unpredictable, and by ensuring a safe airway, the endoscopist can focus on completing the procedure to achieve haemostasis without distraction. Patients should be ideally managed post endoscopy in a critical care setting because they frequently develop hepatic encephalopathy and other features of hepatic decompensation that requires close monitoring and treatment (2).

Endoscopic variceal band ligation is the first line treatment in oesophageal variceal haemorrhage. Small bands are applied to the columns of varices in the distal 5cm of the oesophagus in order to eradicate the column. When endoscoping a patient with suspected variceal bleed, the endoscopist should carefully examine the oesophagus looking for signs of recent bleeding. This is often fibrin clot on the varix that looks like a “nipple”. If this is identified, the endoscopist should take care not to dislodge this clot as this may lead to active bleeding. If this is identified, it may be appropriate to remove the endoscope and then reintubate with the bander in-situ and place a band over the fibrin clot on the varix. The rest of the GI tract can then be examined knowing you are less likely to precipitate active bleeding.

For active oesophageal bleeding, try to place a band over the site of bleeding. If bleeding continues despite this, then place bands carefully over each varix as close to the GOJ as you can. This will increase the tension of the oesophageal wall to help seal the bleeding point. Blood flows from the stomach up the oesophageal varices, therefore placing band close to the GOJ is most effective. It is better to place fewer bands in good positions. Usually, 3 or 4 well placed bands is most effective. Placing more bands than this increases the risk of re-bleeding from banding induced ulcers.

If no clear signs of bleeding are identified in the oesophagus then look carefully in the stomach for bleeding sites. Frequently, the stomach will have blood and clots present obscuring views of part of the stomach. It is important to try and obtain good views of the cardia and fundus to examine for stigma of gastric variceal bleeding. Treatment of gastric varices is discussed below. If no clear site of bleeding is found in the upper GI tract and the patient has evidence of oesophageal varices, then these should be banded to reduce risk of re-bleeding. The optimum interval for repeat endoscopy is unclear, but one study showed that repeating banding at monthly intervals was effective (8).

Endoscopic tissue adhesive injection is recommended for bleeding gastric varices (2). Glue (most commonly Histoacryl) is injected into the varix, with an initial haemostasis rate of 86-100% and re-bleeding rates of 7-28% (2). Complications following glue injection are rare, but include cerebral or pulmonary embolization of glue, and re-bleeding following extrusion of glue casts and sepsis (9). The preparation of glue is complex and requires an experienced assistant, which can make this a technically demanding procedure, particularly if performed out of normal working hours. A video of gastric variceal treatment with glue is shown here (10). There has been a recent problem with the supply of Histoacryl so many units are using Throbmin as an alternative.

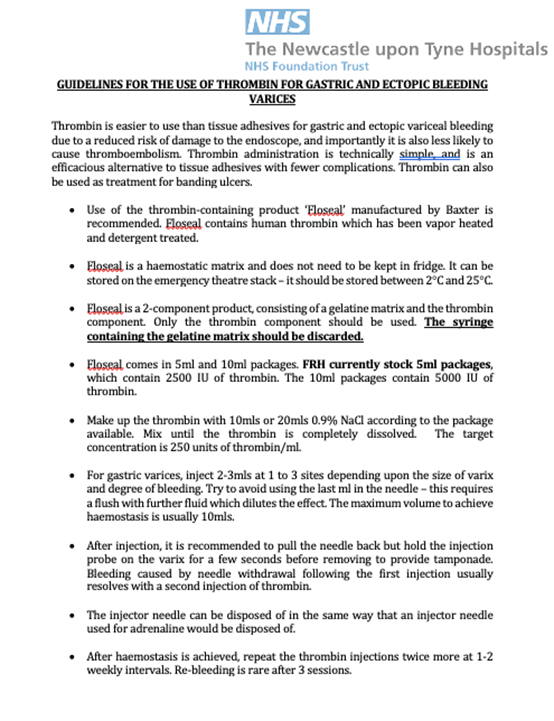

Thrombin injection is a good treatment for bleeding gastric varices. It converts fibrinogen to a fibrin clot and therefore promotes haemostasis within the varix. It has been shown to be safe for use in the management of gastric variceal bleeding and is both simpler to use and has fewer complications than glue (11). An example of protocol for the use of Thrombin is shown in Figure 2. Thrombin and glue have been shown to be comparable with regards to haemostasis rates, however rebleeding rates may be higher with Thrombin (11).

Figure 2: Guideline for the use of thrombin for gastric and ectopic bleeding varices (12)

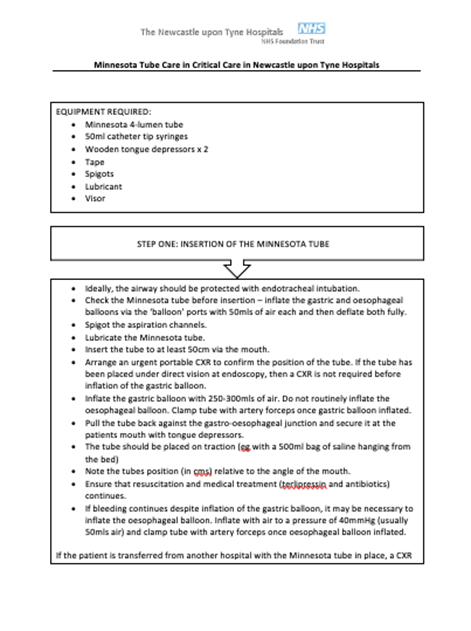

If bleeding is difficult to control from oesophageal or gastric varices, a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (or equivalent such as a Minnesota tube) can be inserted to tamponade the varices (2). This should be placed for a maximum of 24-48 hours until definitive treatment for the varices can be undertaken. Once placed, the gastric balloon should be inflated initially, with the oesophageal balloon inflated only if bleeding is not controlled with inflation of the gastric balloon.

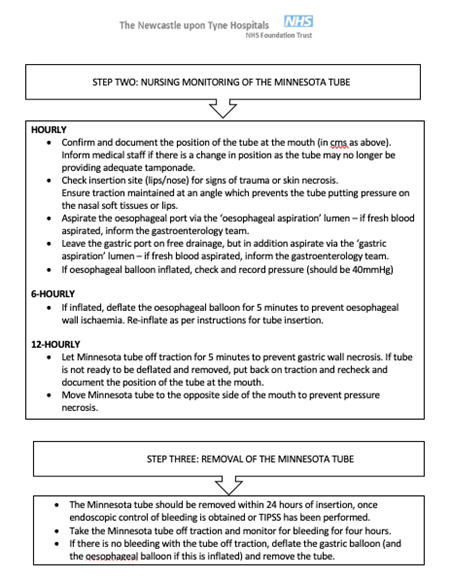

An example protocol for the use of a Minnesota Tube is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Protocol for use of a Minnesota tube for refractory variceal bleeding (13)

Danis stent has been recommended by NICE as an alternative to the Sengstaken-Blakemore tube for treating acute oesophageal variceal bleeding in patients refractory to first line intervention (14). This is a self-expanding metal stent which compresses oesophageal varices. It can be left in situ for up to two weeks and can be either a palliative procedure or used as a bridge to definitive treatment (4). It has no role in the treatment of bleeding gastric varices. Danis stent can be cost saving when compared to Sengstaken-Blakemore tube as it reduces the length of stay in Intensive Care. The placement of the stent requires some training. A video showing the technique for placing the Danis stent is shown here (10).

For refractory gastro-oesophageal bleeding, placement of a TIPS should be considered (Salvage TIPS). Failed endoscopic therapy is defined as refractory bleeding despite 2 attempts at endoscopy. In patients who are eligible for TIPS, further endoscopy is futile, and patients should be discussed with at their local TIPS centre at the earliest opportunity. TIPS may be futile in patients with advanced cirrhosis (Child Pugh score >13 or MELD >30) (4) (15) or in patients who have aspiration pneumonia. Other contraindications for TIPS include: severe heart failure, significant pulmonary hypertension, rapidly progressive liver failure, severe hepatic encephalopathy, uncontrolled sepsis, unrelieved biliary obstruction, polycystic liver disease and extensive primary or secondary hepatic malignancy (4). For patients with very advanced cirrhosis with refractory bleeding who are not eligible for TIPS, the prognosis is very poor and early palliative care should be initiated.

Balloon occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (B-RTO) is a procedure which can be considered as an alternative to TIPS for bleeding gastric varices. This procedure involves insertion of a balloon catheter to stop blood flowing in outflow shunts. The veins draining gastric varices are then embolised with microcoils (2).

Oesophageal bands will fall off approximately 3 – 7 days after oesophageal banding, with subsequent development of oesophageal ulceration (16). Bleeding from oesophageal banding ulceration is reported to be 3.6% (16). There are currently no guidelines for treatment of this complication, although treatments for this have included cyanoacrylate or thrombin injection, further variceal banding, and placement of TIPS (16). A small study retrospectively reviewed 430 patients who had undergone variceal banding, and found that 33 patients developed bleeding from banding ulcers as a complication. These patients were treated with further variceal banding (24.2%), cyanoacrylate injection (18.2%), APC (3%), Sengstaken Blakemore tube (9.1%), or PPI therapy alone (45.5%).

Following variceal bleeding, patients should be initiated in NSBB or carvedilol (initially at a dose of 6.25mg daily, increased to 12.5mg daily if tolerated) when their cardiovascular status is stable and terlipressin has been withdrawn. In addition, patients should be entered onto a variceal banding programme to eradicate the oesophageal varices (4).

The role of pre-emptive TIPS is beyond the scope of this review, but further information on this is available (4).

Conclusion

Acute upper GI bleeding is a common presentation on the acute medical take. Initial focus should be on appropriate resuscitation of patients and on timely, safe endoscopy. Options to treat variceal bleeding include band ligation, tissue adhesive or thrombin injection, Danis stent insertion and TIPS placement.

Author Biographies

Lisa McNeill

Lisa is a Northern Irish GI ST7. She is the NI BSG Trainee section representative and has been actively involved with the section over the past few years, including co-leading the Taster Course 2023. She is particularly interested in Hepatology and has completed the Hepatology NTN at the Freeman Hospital, Newcastle Upon Tyne.

Dr Stuart McPherson

Dr Stuart McPherson is a Consultant Hepatologist, Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer, and Head of Department for Liver Medicine at the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals. He completed undergraduate medical training at St Andrews and Manchester Universities and subsequently undertook specialist training in Glasgow and Newcastle. In addition, Dr McPherson spent two years in Brisbane, Australia researching hepatitis C and fatty liver disease. Apart from ongoing research in the early diagnosis of NAFLD and the prevention of cirrhosis, he also serves as the Chair of the BSG/BASL NAFLD Special Interest Group.

CME

Endoscopy Workforce Education and Training

30 January 2024

Investigations of IDA – When, how and when not to!

03 January 2024

Masterclass: Endoscopic foreign body removal – what you need to know

11 December 2023

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acute upper GI bleeding in over 16s: management [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2022 Apr 7]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg141

- Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Patch D, Millson C, Mehrzad H, et al. UK guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut. 2015 Nov;64(11):1680–704.

- Iwakiri Y. Pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 2014 May;18(2):281–91.

- de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, Reiberger T, Ripoll C, Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII – Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2022 Apr;76(4):959–74.

- Stuart McPherson, Jessica Dyson, Andrew Austin, Mark Hudson. Decompensated Cirrhosis Care Bundle – First 24 hours [Internet]. British Society of Gastroenterology. 2014. Available from: https://www.bsg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/BSG-BASL-Decompensated-Cirrhosis-Care-Bundle-First-24-Hours.pdf

- Siau K, Hearnshaw S, Stanley AJ, Estcourt L, Rasheed A, Walden A, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)-led multisociety consensus care bundle for the early clinical management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020 Jul;11(4):311–23.

- O’Shea RS, Davitkov P, Ko CW, Rajasekhar A, Su GL, Sultan S, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guideline on the Management of Coagulation Disorders in Patients With Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1615-1627.e1.

- Wang HM, Lo GH, Chen WC, Chan HH, Tsai WL, Yu HC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of monthly versus biweekly endoscopic variceal ligation for the prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding: Ligation performed monthly versus biweekly. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Jun;29(6):1229–36.

- Cheng L, Wang Z, Li C, Lin W, Yeo AET, Jin B. Low Incidence of Complications From Endoscopic Gastric Variceal Obturation With Butyl Cyanoacrylate. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010 Sep;8(9):760–6.

- Danis stent animation [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rbYext0cvg

- Lo GH, Lin CW, Tai CM, Perng DS, Chen IL, Yeh JH, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of thrombin versus cyanoacrylate injection in the control of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopy. 2020 Jul;52(07):548–55.

- Newcastle Hospitals Liver Unit. Guidelines for the use of Thrombin for Gastric and Ectopic Bleeding Varices. 2023.

- Newcastle Hospitals Liver Unit. Minnesota Tube Care in Critical Care in Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals. 2023.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Danis stent for acute oesophageal variceal bleeding. 2021 Mar [cited 2022 Apr 7]; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg57

- Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, Travis S, Armstrong MJ, Tsochatzis EA, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut. 2020 Jul;69(7):1173–92.

- Cho E, Jun CH, Cho SB, Park CH, Kim HS, Choi SK, et al. Endoscopic variceal ligation-induced ulcer bleeding: What are the risk factors and treatment strategies? Medicine. 2017 Jun;96(24):e7157.